https://www.wkyt.com/2024/02/08/kentucky-pro-football-hall-fame-announces-class-2024/

Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame is celebrating their 20th Induction Class

Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame to benefit Salvation Army Boys & Girls Club of the Bluegrass; and

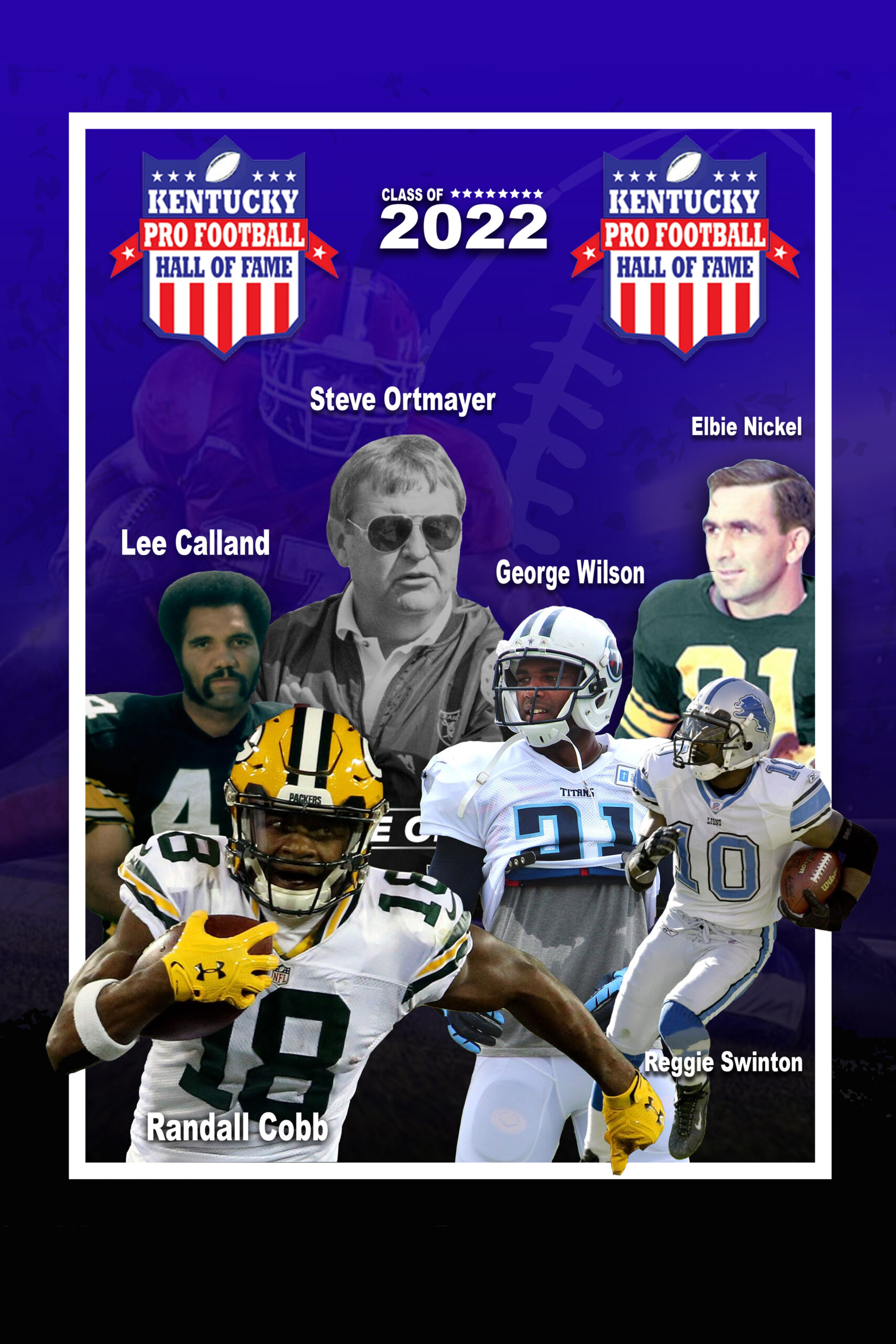

2022 inductees and Blanton Collier Award for Integrity

(Lexington, Kentucky) – The Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame is celebrating their 20th Induction Class slated for June that will benefit the Salvation Army Boys & Girls Club of the Bluegrass.

The Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame is excited to announce we will be inducting the following into our Hall of Fame:

Randall Cobb, George Wilson, Jr., Reggie Swinton, Elbie Nickel, Coach Steve Ortemayer, and Arthur Lee Calland.

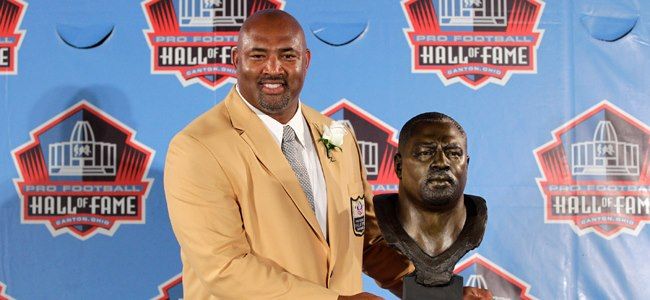

The Blanton Collier Sportsmanship Group will also be giving their award for integrity to NFL and KY Pro Football Hall of Famer Dermontti Dawson.

The official induction ceremony weekend will take place in Lexington, Kentucky, with the hall of farmers receiving their Hall of Fame jackets from the mayor of Lexington followed by a bourbon bottle signing and ring ceremony on Thursday, June 23rd at Limestone Hall. The public is invited to the jacket ceremony and to purchase bourbon bottles autographed by our Hall of Fame members and inductees. “We are excited to welcome back all of our Hall of Famers to receive their jackets and help induct our 2022 class.”, says Executive Director Franky Minnifield.

On June 24th the first ever statewide charitable golf outing will culminate with the championship round to be played at Kearney Hills Golf Links. The winners will receive an all expense paid trip to the 2023 Super Bowl in Glendale, Arizona.

“Kentucky is the only state in the country with a pro football hall of fame,” said Dr. Kay Collier McLaughlin, chair of the Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame, Inc. board of directors. “We’re in a unique position to recognize great accomplishments in football, but also have as our main objective to offer financial assistance to organizations that enrich the lives of children.”

Proceeds from the 2022 Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame Induction ceremony and golf outing will support the Salvation Army Boys & Girls Club of the Bluegrass. “We, at The Salvation Army Boys & Girls Club, are excited about the opportunity to join with the Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame to enhance our ability to impact youth in our community. The Kentucky Pro football Hall of Fame consists of highly motivated, highly successful individuals who have a passion for investing in kids, just like we do. We believe this opportunity will allow us to increase and improve the numerous activities we make available to our Club members every day and also allow our Club members to meet and be inspired by some of their heroes. We thank the Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame for this opportunity and look forward to all that we might accomplish together for the youth of Lexington” said Major William Garrett of the Salvation Army of the Bluegrass.

Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame

“We’re excited about our relationship with Salvation Army Boys & Girls Club of the Bluegrass whose purpose is to increase the quality of life for children from Kentucky and throughout the world, “said Collier-McLaughlin.

inducted into the Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2022 are:

| NAME/HOMETOWN | HIGH SCHOOL | COLLEGE | NFL TEAM |

| Randall Cobb

Hometown: Maryville, TN |

Alcoa High School in Alcoa, Tennessee | University of Kentucky | Houston Texans

Green Bay Packers |

| George Eugene Wilson

Hometown: Paducah, Kentucky |

Paducah Tilghman High School | University of Arkansas | Buffalo Bills

Tennessee Titans |

| Reggie Swinton

Hometown: Little Rock, Arkansas |

Little Rock Central High | Murray State University | Dallas Cowboys, Detroit Lions and Arizona Cardinals. |

| Lee Calland

Hometown: Louisville Kentucky |

Louisville Central High | University of Louisville | Pittsburgh Steelers

Atlanta Falcons Minnesota Vikings |

| Steve Ortmayer

Hometown : Painesville, Ohio |

Nashville, Tennessee | Vanderbilt, La Verne | Oakland Raiders |

| Elbert Nickel

Hometown : Fullerton, Kentucky |

South Shore, Kentucky | University of Cincinnati | Pittsburgh Steelers |

The legendary Dermontti Dawson will receive the 14th annual Blanton Collier Award for Integrity, named after the famous UK and Cleveland Browns coach. The award recognizes individuals who have shown outstanding integrity both on and off the field. Dermontti Dawson (born June 17, 1965), is a former American football offensive tackle who played 13 seasons for the National Football League‘s Pittsburgh Steelers. Dermontti is widely considered to be one of the greatest offensive linemen in NFL history. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2012.

Sponsorship packages for the 2022 Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame induction ceremony and golf outing as well as golf teams are currently available through the Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame at 859-276-3488. For more information please go to www.kyprofootballhof.org.

| Mission Statement. The purpose of the KY Pro Football Hall of Fame is to appropriately honor persons that

have brought significant recognition to the state of Kentucky. |

NFL Player Salaries Are Not What They Seem: A Realistic, Historical Perspective on the NFL & Player Salaries.

A realistic, historical perspective on the NFL and player salaries.

$17,500 – the salary of a South East Conference head football coach in 1961. $50,000 – the highest salary ever earned by Jim Brown, the greatest running back the game of pro football has ever known.

There was a time when even major university cheerleaders had a squad of only ten members and they purchased their own skirts. That one uniform would have to last all four years. A pro football staff of seven coaches was the average in the early ’50’s.

Hard to believe, isn’t it? Today, as the salaries of college coaches soar into the stratosphere and fledgling players demand and receive a signing bonus. It’s all hard to remember. The current headlines about pro athletes would have us believe that they are all millionaires, living large.

When professional football began in the 1920’s it was a world of shoestring budgets. Teams played an average of six games a season with players returning to their day jobs on Monday morning. By the mid 1960’s it was still necessary for even members of a championship team to have a real job in the off season.

Take the 1964 pre-Super Bowl Cleveland Browns. Hall of Fame defensive end Willie Davis taught mechanical drawing. Jim Houston, the 1960 first round draft pick sold insurance. Guard Chuck Noll, who would become a Hall of Farmer for his coaching success in Pittsburgh, was a salesman for Trojan Freight Lines. Lou ‘The Toe’ Groza was also in the insurance business. John Wooten taught junior high school and even the legendary Jim Brown was a marketing representative for Pepsi.

In 1892, the first paid player, William ‘Pudge’ Hoffelfingef was paid $500 cash for his efforts on the field before returning to the steel mills. The famous Jim Thorpe received $250 a game from the Canton Bulldogs. The work was regional and unstable. Players were sought who could play both sides of the ball and were expected to be big enough and strong enough for both offense and defense. Free substitution was the name of the game. Through the mid-1940’s it was a white man’s game. In 1946 – a year before Jackie Robinson made history in Major League Baseball – Los Angeles and Cleveland each signed two African American players. On the road they would be required to sleep in separate hotels from the rest of the team.

Football as a career only began to emerge in the late 1960’s. As one player of the era said, “Year round training was unheard of. We had to pay our bills and then get in shape before training camp started.” By 1969 the average salary for a ten game season, with three pre- season games and a month long training camp was $25,000. With inflation figured, that would be $156,400 by today’s figures. Ticket prices for a pro game ranged from $31-$38 with sales providing 60% of the team’s income. Average revenue per team was $3.8 million. As late as 2008, veterans of the game were often left with permanent disabilities, and lack of ability to pay their medical bills.

The decade of the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s saw societal changes that would impact the sports world dramatically, with pro football behind Major League Baseball, basketball and even hockey. It began, quite naturally, with competition, as leagues like the AFL, the USFL and Canadian football demanded more collegiate players be available to play at the next level. The free substitution rule was banned in 1949 and rosters grew as more specialization was required to provide adequate offense and defense. Promising rookies began demanding more money to sign with a team and veterans grew restless with the realization that their years of service were not being fairly rewarded. At the same time, technological advances meant that television was exercising more control over sports scheduling and even time outs for advertisements. By 1984 as the legendary Jim Brown, long retired, made plans for a foot race with current stars Walter Peyton and Franco Harris, he observed that participating in the race had nothing to do with whether or not his records would be broken. It had to do with pointing out that in his day records were set in a 10 game schedule without tv timeouts.

Facts are facts. Pro football players have a short and risky career. The average player is active for 3.2 years. One half of veterans retire with permanent disability. They have a life expectancy of 55 years – far less than the average 70. It’s important to maximize earning ability during short careers.

By 1984 the New York Times wrote a story saying that the most important line in pro football had become the bottom line for owners. TV revenue was soaring and under a profit sharing agreement, teams were receiving $5 million each. Sports agents became a part of the scene, negotiating big contracts for rookies who had yet to play a pro game. Established players followed suit, with New York Jets defensive lineman Mark Gastineau negotiating an unheard of five year contract for $3.71 million, known as the “Gastineau deal,” and John Elway quarterbacking his way to a five year $5 million contract. Under the existing rules, players were under a reserve clause which saw their careers managed under one team. Under the “Rozelle Rule” changing teams meant that the new team had to pay compensation to the former team. Through 1975 only four players moved. The popularity of the sport continued to rise, fueled by TV coverage and the new practice of endorsement deals.

It was inevitable that players would want a larger share of the very profitable pie that was baking for the owners and so the NFL Players Association was formed to protect the rights and the future of the athletes and to give players some power in the system. The resulting free agency and a greater percentage of revenue were a major step forward. Collective bargaining was often tough as owners were protective of their bottom lines. There have been several major strikes. Today, the NFL has salary caps and while average salaries may sound quite high in comparison with those of the average fan, today’s experienced players know it is highly possible that they (and their comfortable salaries) will be expendable as a younger, less experienced and hungry-for-action player can come in well under that cap. This is not much different from the corporate world.

Pro football is a business. It is a business which provides entertainment for hundreds of thousands of people every autumn. It is also a business where the players – those gifted with the physical, mental and emotional skills to play at that highest level of sport- provide the services that make the TV deals and the bottom lines possible for the short amount of time that they are physically able to do the job. The majority of these players utilize the platform of their playing days not only to play the game they love, and maximize their earning ability and prepare for life after the game, but also to contribute to their communities, raise money for charities, and inspire young people.

The Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame began with players whose stories were written well before the days of signing bonuses and big bucks. Each year it continues to honor men from that early era, as well as those who were part of the evolution of the game. They did not become millionaires. They are the shoulders the modern game stands on and they are still giving their names and their time and energy to support Kentucky’s children through the Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame charities. Their compensation is the light in a child’s eyes when they encounter one of the greats at the Salvation Army’s Boys and Girls Club; the awe that makes a young man dig deeper when he sees the HOF ring on the hand of one of yesterday’s heroes, or today’s champions.

So why support an event which honors “Kentucky’s football legends”? For starters, so that folks know that we in Kentucky are worth a lot more than fast horses and great bourbon. Long known for our college basketball prowess, pro football might have seemed an also – ran to the uninitiated. When you support the Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame you are not only supporting Kentucky’s children, you are saying thank you in a tangible way to the men who gave all of us the greatest game and who continue to show up long after their playing days are over – gimpy knees and all.

by Kay Collier McLaughlin

click on this link to see Kay’s interview with Raymond Smith about this topic:

Links to all Articles about 2016 Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame & All-Commonwealth Team

- http://www.kentucky.com/sports/college/kentucky-sports/uk-football/article72840432.html

- http://www.kentucky.com/sports/college/kentucky-sports/uk-football/article58758043.html

- http://www.wkyt.com/content/sports/Five-to-enter-Kentucky-Pro-Football-Hall-of-Fame-367892761.html

- http://gridironnow.com/2-uk-ties-inducted-kentucky-pro-football-hall-fame/

- http://www.kentucky.com/sports/college/kentucky-sports/uk-football/article85604302.html

- http://eaglecountryonline.com/local-article/thomas-mores-meyer-named-commonwealth-team/

- http://www.journal-times.com/sports/college_sports/three-knights-named-to-kentucky-collegiate-all-commonwealth-team/article_33d6e48e-3303-11e6-93d0-37559b73a2b1.html

- http://www.lex18.com/story/32257089/jon-toth-selected-to-2016-all-commonwealth-team

- http://www.goracers.com/news/2016/4/19/football-four-racers-named-to-all-commonwealth-team.aspx

- http://www.wkyt.com/content/sports/Three-EKU-players-named-All-Commonwealth-379043291.html

- http://www.wymt.com/content/sports/Three-Bulldogs-named-to-All-Commonwealth-team-376758611.html

- http://www.kwcpanthers.com/news/2016/5/12/football-keelan-cole-named-to-all-commonwealth-team.aspx

- http://www.msueagles.com/news/2016/4/20/four-football-eagles-named-to-all-commonwealth-team.aspx?path=football

- http://www.ekusports.com/news/2016/5/8/football-three-colonels-earn-all-commonwealth-honors.aspx

- http://tmcsaints.com/sports/fball/2016-17/releases/20160627jdgisg

- http://centrecolonels.com/sports/fball/2015-16/releases/20160419knj1f2

- http://www.campbellsvilletigers.com/article/5727.phphttp://upikebears.com/news/2016/4/19/football-trio-named-to-all-commonwealth-team.aspx

- http://www.cumberlandspatriots.com/article/5886.phphttp://www.lindseyathletics.com/article.php?articleID=8003&skipSplash=1

- http://www.lindseyathletics.com/article.php?articleID=8003&skipSplash=1

Herald-Leader Staff Report: KY PRO FOOTBALL HALL 2016 CLASS

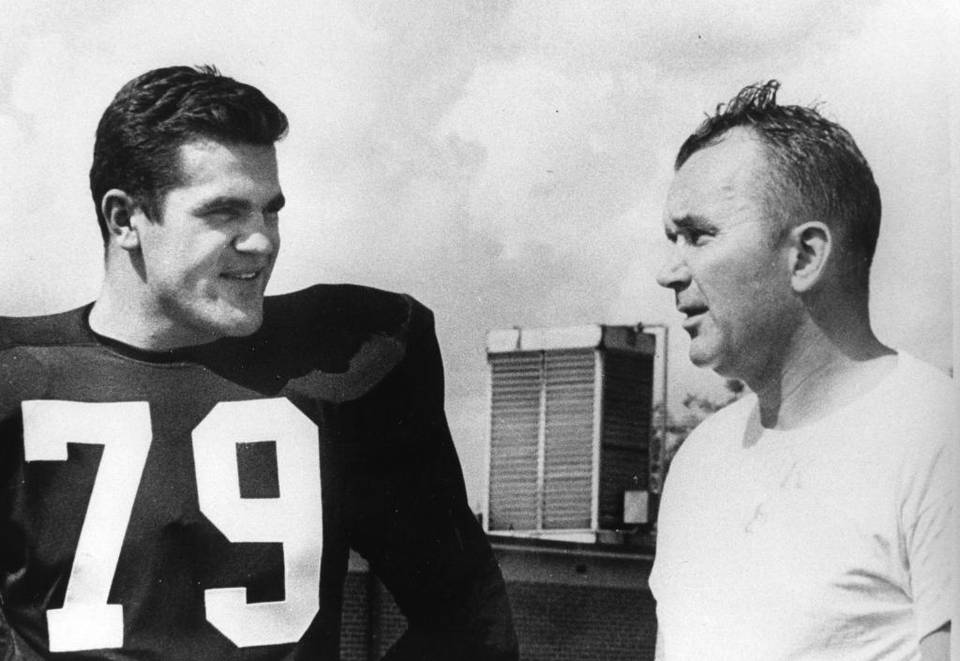

Blanton Collier, with UK player Lou Michaels,

2016 Ky Pro Football Hall

Former University of Kentucky coach Blanton Collier was among five new inductees named Friday to the Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame.

The 2016 class also includes former Kentucky State defensive end Council Rudolph, former UK tackle Warren Bryant, former Eastern Kentucky safety Myron Guyton and former Louisville safety Ray Buchanan.

Also during the induction ceremony, former UK player and U of L coach Howard Schnellenberger will receive the 10th annual Blanton Collier Award for Integrity.

“Kentucky is the only state in the country with a pro football hall of fame,” said Dr. Steve R. Parker, chair of the Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame Inc. board of directors. “We’re in a unique position to recognize great accomplishments in football, but also have as our main objective to offer financial assistance to organizations that enrich the lives of children.”

Collier, from Millersburg, Paris High School and Georgetown College, coached UK from 1954-61 and is the last Wildcats coach to post a winning career record (41-36-3) at Kentucky. He went on to coach the Cleveland Browns. He died in 1983.

Rudolph, from Anniston, Ala., played in the NFL for the Houston Oilers, St. Louis Cardinals and Tampa Bay Buccaneers in the 1970s.

Bryant, who played at UK from 1973-76, went on to an NFL career that included stops with the Atlanta Falcons and Los Angeles Raiders.

Buchanan, from Chicago, played for the Colts, Falcons and Raiders in a career that ended in 2004.

Greg Cote: Howard Schnellenberger deserves to get into College Football Hall of Fame Read more here

BY GREG COTE

A ballroom full of appreciative admirers and those impacted by Howard Schnellenberger’s epic coaching career will gather Thursday evening in Davie to say thanks in a much deserved “tribute and celebration dinner” put on in his honor by the Miami Touchdown Club.

Suffice to say, the folks running the College Football Hall of Fame would not be impressed.

See, Schnellenberger isn’t good enough for them.

He was good enough to put the University of Miami on the map and kick off a modern dynasty by being the Hurricanes’ first national-championship football coach in 1983.

He was good enough soon after to take over a moribund University of Louisville program and turn it around, too, leaving it with a new stadium and a bright future.

He was good enough to be the god of football at Florida Atlantic University, the program’s creator, building it from nothing, and leaving it with a great little campus stadium built by his own imagination, perseverance and fundraising acumen.

Howard Schnellenberger, now 81, was good enough to be part savior, part hero and a lasting, revered icon at three institutions.

He was good enough to win 158 college football games in his career and be a perfect 6-0 in bowl games.

And that’s not even getting to his work before becoming a head coach. That included an assistant’s role under the tutelage of Bear Bryant at Alabama, where Schnellenberger was good enough as a recruiter to reel in a couple of quarterbacks named Kenny Stabler and Joe Namath.

As player or coach, Schnellenberger devoted 39 years of his life to college football across six decades and would grace the coaching Mount Rushmore of three programs.

But he isn’t good enough for the sport’s Atlanta-based Hall of Fame, administered by the National Football Foundation, on account of one stringent rule in its criteria for consideration: That inductees have at least a career .600 winning percentage.

Schnellenberger falls short, yes. He lost almost as many games (151) as he won. That can happen to a man’s career ledger when the three programs he turned right — Miami, Louisville and FAU — were nothing (figuratively or literally) before he arrived and it took some time, and rough seasons, to make it all work.

He didn’t inherit champions. He took on challenges.

He didn’t move into palaces. He took on fixer-uppers … and built them to last.

It is appropriate Schnellenberger’s testimonial dinner is on the same day UM conducts its first fall practice, because much of the pressure on current Canes coach Al Golden is on account of the standard Schnellenberger set, the bar he raised.

Likewise, every Louisville coach will know who he’s following, just as every FAU coach will know who the father of that program is and always will be.

How can there be more than 1,100 players and coaches in this Hall but be no room for Schnellenberger?

The College Hall of Fame should make an exception to its 60 percent rule because Schnellenberger is deserving, and also because the rule is arbitrary and unnecessary.

I spoke at length about this with Steve Hatchell, president and CEO of the NFF and college Hall. If you think you know the name, he was Orange Bowl Committee executive director from 1987 to ’93. He knows Schnellenberger’s heft and imprint better than most.

Hatchell was sympathetic but unbending.

Quick background: In 1990 the Hall went “hard and fast,” Hatchell said, on the criteria that coaches admitted must have won at least 100 games and won 60 percent. That rule was “fortified again” by the Hall’s board of directors, he said, in 2012.

But before and in between, plenty of coaches who won less than 60 percent — 32 of them, to be exact — were inducted into the Hall.

As recently as 2005, a “sub-60” exception was made to induct coach Willie Jeffries of Mississippi Valley State.

You don’t make exceptions and then say, “We don’t make exceptions.”

“Would I like to see exceptions here and there? Sure,” Hatchell told me. “But when and where do you draw the line?”

Answer: You consider very few exceptions. But when a candidate has won 150-plus game, won a major national championship and earned legend’s status at three schools — you consider him.

The issue here, though, goes beyond that 60 percent rule.

It involves who is pushing Schnellenberger for induction and how.

It happens to be the wrong people and the wrong way.

A well-meaning group of supporters led by major FAU booster John Sasko has undertaken a letter-writing and media campaign to exert pressure to induct their guy. They even elicited a glowing letter of support from Don Shula sent May 18 to the Hall’s selection committee members.

The trouble is, this effort, what Hatchell called “waging a campaign,” is rubbing wrong some of the very people who need to be convinced to make an exception for Schnellenberger.

A better effort more likely to succeed would be one done through accepted channels, starting with an official nomination of Schnellenberger by a school. That’s a prerequisite, but neither UM, Louisville nor FAU has done this, perhaps because each knows of the 60 percent rule that would exclude him.

FAU has nominated Schnellenberger for an Outstanding Contribution to Amateur Football award, which is more likely to happen but clearly would be a consolation prize to full Hall induction.

Hatchell said the NFF and Hall would “review” their no-exceptions rule this fall. Meantime, the presidents or athletic directors of UM, Louisville or FAU — or all three — should formally and officially nominate Schnellenberger for induction and make clear the compelling reasons why he is deserving of an exception to their criteria.

That is where the effort to give Schnellenberger his just reward must begin.

That is the only way it might happen, and happen it should.

Read more here: http://www.miamiherald.com/sports/spt-columns-blogs/greg-cote/article30184617.html#storylink=cpy

Schnellenberger deserves entry into Hall of Fame

WEST PALM BEACH, Fla. — Howard Schnellenberger has an autobiography coming out Sept. 1 titled Passing the Torch. The only greater wish I could imagine would be an audiobook with the coach himself booming out every word.

This guy has more epic tales to tell than Mark Twain, and almost as many unforgettable characters to introduce on the river of his life.

Schnellenberger played at Kentuck

y from 1952 to 1955 and was a UK assistant coach in 1959-60. He played and worked for Bear Bryant. He recruited Joe Namath to Alabama, at one point writing bad checks to transport the star prospect to Tuscaloosa before somebody else could snap him up. Schnellenberger was the offensive coordinator for Don Shula’s perfect 1972 Dolphins, too, and the visionary who started the University of Miami’s national championship tradition.

Add it all up, with the resurrection of Louisville’s program and the birthing of Florida Atlantic’s thrown in, and there’s only one big-time minus.

Schnellenberger, 80, keeps getting passed over for induction in the College Football Hall of Fame. There’s no real logic to that, but there is a technical reason.

The National Football Foundation requires that coaches have a .600 career winning percentage to be eligible. Schnellenberger got off to a great start at Miami (41-16 and a national title in 1983), but his willingness to take on the long, hard work of building other programs from the bottom left his college career record at 158-151-3, barely over .500.

There’s a way to bypass this problem. The Hall of Fame has a special committee that examines “unique cases.” If anyone in college coaching qualifies more than Schnellenberger, or has been more famous, for that matter, at the peak of his powers, it must be a very short list.

Two coaches made the grade when the 2014 induction class was announced May 22 — Oregon’s Mike Bellotti and Appalachian State’s Jerry Moore. The former won a couple of Pacific-10 championships in 14 years of major-college coaching. The latter won three consecutive national titles with a powerhouse small-school program but never had a winning record in five seasons at Texas Tech.

Successful coaches, sure, but hardly on a scale beyond Schnellenberger’s reach.

Schnellenberger, a former NFL head coach at Baltimore, didn’t drop down to that small-college level until he was 67, and that was to inaugurate the program at Florida Atlantic. Even then, he had the Owls up to FBS status by their fifth season. The easy way just never had much of an appeal.

That’s really the point here. Schnellenberger shouldn’t be punished by the Hall’s eligibility criteria for taking on the worst jobs and transforming them into something grand. Miami football had lagged so badly before Schnellenberger’s arrival that not even a visit by Notre Dame could guarantee 25,000 fans at the Orange Bowl in 1975.

Louisville, likewise, was an overlooked independent until Schnellenberger arrived to push the Cardinals to a Fiesta Bowl rout of Alabama. This fall Louisville begins play in the ACC, operating from a football complex that bear Schnellenberger’s name.

The Florida Atlantic epilogue to this story features construction of an on-campus stadium that only Schnellenberger could have made happen. Miami could have had one, too, if school officials had trusted his instincts and direction.

Look to the Bear for Schnellenberger’s inspiration in all things.

Maryland was coming off a 1-7-1 season when Bryant got there in 1945. The Terrapins promptly went 6-2-1 and lost their hot young coach to Kentucky.

The Wildcats had not won more than six games in a season since 1912 at that point, but Bryant got them to 7-3 in his first season. From 1949-51, Kentucky played in the Orange Bowl, the Sugar Bowl and the Cotton Bowl. The program hasn’t been to a major bowl since.

Texas A&M got a similar boost from the Bear, and next came Alabama, which was 4-24-2 in the three seasons before Bryant’s hiring, with a 17-game losing streak included in that skid. Three seasons into the Bryant era, the Crimson Tide was 11-0 and celebrating a national championship.

Schnellenberger showed the same boldness in signing up for ugly assignments, and the similar belief that he could turn any situation around. Other than stubbing his toe during one 5-5-1 season at Oklahoma, it worked. Not on the scale of Bryant’s success, of course, but it worked.

If the Hall of Fame can’t see the value in that, then the people who run that show are outsmarting themselves. That’s a shame for Schnellenberger, who belongs on any list of men who have made college football shine.

Read more here: http://www.kentucky.com/2014/07/31/3360048_schnellenberger-deserves-entry.html?rh=1#storylink=cpy

Tom Jackson, 2015 Pete Rozelle Award winner

Congrats to Kentucky Pro Football Hall of Fame member Tom Jackson, who is the 2015 Pete Rozelle Radio-Television Award winner as selected by the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Tom was hired as an ESPN studio analyst in 1987 and has excelled ever since that time. He was a Pro Bowl linebacker during his years with the Denver Broncos (1973-86) before moving into the ESPN role. Tom will be honored during Hall of Fame ceremonies next month.

Bill Arnsparger had passed away at the age of 88.

Bill Arnsparger was inducted in to the Ky Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2010 is Pictured here with Miami Dolphins head football coach Don Shula

For a town of less than 10,000 people known for its famous Thoroughbred horse farms, Paris, Ky., holds an important if underrated place in the annals of football coaching.

We were reminded of this Friday when the news came that Paris native Bill Arnsparger had passed away at the age of 88.

Renowned as the architect of the “No Name Defense” of the 1970s that helped Don Shula’s Miami Dolphins to two Super Bowl titles — including the perfect 17-0 season of 1972 — as well as the Dolphins’ “Killer Bs” defenses in the 1980s, Arnsparger was one of the game’s greatest defensive minds.

He coached on teams that went to six Super Bowls. He won the 1986 SEC title as LSU’s head coach. Later, as athletics director at Florida, he hired Steve Spurrier as the Gators’ football coach before returning to the pro ranks to help the San Diego Chargers to the 1994 AFC title.

In the name of full disclosure, my late father and Arnsparger were friends that grew up together in Paris. My father took great pride in Arnsparger’s accomplishments. Everyone in Paris did.

Actually, this all goes back to another famous Paris coaching product, Blanton Collier. Arnsparger played both football and basketball for Collier at Paris High School before Collier went on to be the head coach at Kentucky and later the Cleveland Browns (where he won an NFL title in 1964 and earned a reputation as an exceptional teacher of the game).

“If Paul Brown is known as the organizer, and Vince Lombardi the motivator, then Blanton Collier has to be known as the teacher of record,” Paul Zimmerman, author and pro football writer for Sports Illustrated, once wrote.

In 1944, during World War II, Collier was sent to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station outside of Cleveland. Paul Brown, then coach at Ohio State, coached the base’s football team and noticed Collier would attend practice daily to watch from the sideline. When Brown learned the dedicated observer was a high school coach from Kentucky, he asked Collier to assist.

Then after the war, Brown became coach of the upstart Cleveland Browns and hired Collier as an assistant. As it happened, a young Don Shula played defensive back for the Browns in 1951 and 1952.

Meanwhile back in Paris, after a stint in the Marines, Arnsparger enrolled at Miami of Ohio where he played for Sid Gillman, George Blackburn and Woody Hayes. Bo Schembechler was a teammate. When Hayes left to become head coach at Ohio State in 1951, he brought Arnsparger and Schembechler along as assistants.

Three years later, Collier returned to Kentucky to succeed Bear Bryant as UK’s coach. He hired Arnsparger and later Shula as part of a historic staff that during Collier’s tenure included seven men — Collier, Arnsparger, Shula, Chuck Knox, John North, Leeman Bennett and Howard Schnellenberger — who later became NFL head coaches.

When UK did not renew Collier’s contract after the 1961 season, Arnsparger spent two seasons at Tulane before reuniting with Shula, then the Baltimore Colts’ head coach, in 1964, and one of the NFL’s greatest coaching tandems was born.

“I’ve known and competed against a lot of great coaches over the years,” wrote Shula in the foreword to Arnsparger’s 1999 book, Coaching Defensive Football, “Yet, even today, when I think of defensive coaches, the first name that comes to mind is Bill Arnsparger. He was special.”

It was Arnsparger who first used situational substitutions, who believed in versatile athletes — hybrids they’re called now — who could play multiple positions.

“I’ve never seen defenses like the one we’ve got,” Bob Brudzinski, a Dolphins linebacker in the 1970s, told Sports Illustrated. “Nobody else runs stuff like we do.”

After the Dolphins won the 1972 Super Bowl, Arnsparger was visiting family in Paris when he gave a talk open to the public. My father took me. I remember two things — the size of Arnsparger’s Super Bowl ring, and something my father said on the way home.

“Bill was tough,” he said. “But I never heard him say a bad word about anyone.”

On Friday, Chargers’ owner Dean Spanos called Arnsparger “a true gentleman.” In the Collier tradition, Arnsparger believed in sportsmanship and preparation, a coach nicknamed “One More Reel” for his incessant film study.

Dick Anderson, the great safety on those Shula/Arnsparger teams of the 1970s, told the Palm Beach Post on Friday that the closest current coach to Arnsparger is Bill Belichick, which makes sense on many levels — both coaches low key, devoted to detail with a genius for unique strategy.

“The man was brilliant,” said Anderson of Arnsparger.

And it all started in Paris.